In our ongoing series, ‘One to Watch,’ we profile the movers and shakers at TI who are making a difference through innovation or citizenship.

German engineer Dietmar Walther pushes boundaries every day; he doesn’t believe in setbacks or constraints.

German engineer Dietmar Walther pushes boundaries every day; he doesn’t believe in setbacks or constraints.

“My motto is, ‘learning from failures is essential,’” he admits.

Finding out how things work is what inspires and drives Dietmar. This puts him in good company with decorated innovator Thomas Edison who famously said, “I have not failed. I have successfully discovered 1,000 ways to NOT make a light bulb."

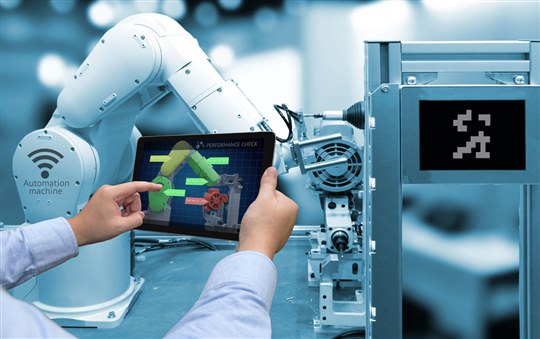

Dietmar was in high school when he first saw how PCs connected using RS-232 cables would quickly pave the way for devices with wireless connectivity.

“Within five or six years, the world completely changed,” he said. “This triggered my fascination to find out how things work, which led to why I became an engineer.”

The delight that people have when they use technology drives Dietmar to continually develop his understanding of technical issues and challenges.

“Innovation is a very, very important thing,” he said. “TI is a strong driver for this. If you innovate in a very creative way, which really helps to solve certain issues in daily life, I think it correlates to good business.”

Dietmar particularly enjoys the variety and unpredictability of his work. “I honestly never know when I come to work in the morning what’s going to happen,” he said. “It never gets boring, and I learn each day.”

Cutting down on the noise

Technically, Dietmar’s daily work involves layout and design analysis, as well as lab and production testing and measurement. But it is his work to advance the understanding of how external electromagnetic interference (EMI) can disturb the operation of devices that established his reputation within our company and helped lead to his election to the TI Tech Ladder as a member of the group technical staff.

Technically, Dietmar’s daily work involves layout and design analysis, as well as lab and production testing and measurement. But it is his work to advance the understanding of how external electromagnetic interference (EMI) can disturb the operation of devices that established his reputation within our company and helped lead to his election to the TI Tech Ladder as a member of the group technical staff.

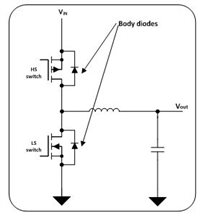

For example, think about when your radio speaker and smartphone are placed too closely together – sometimes this negatively affects operation of one or both devices – making the sound of each fade in and out and buzz or vibrate. This effect is what happens when EMI, also called radio frequency interference (RFI) or “noise” interferes. Technically, EMI is defined as the disruption of one electronic device by another electronic device when they are in the vicinity of each other and electromagnetic fields or radio frequencies collide.

One of the biggest achievements for Dietmar was creating a methodology to characterize the electromagnetic sensitivity of electronic devices. This methodology – Fast Transient Characterization – proved invaluable in tackling problems facing customer product design all the way down to the chip level.

Prior to this new characterization, engineers were looking at the issue of physical damage, reset, or hang-ups from electrostatic discharge (ESD) – the sudden flow of electricity between two electrically charged objects – but only from an overall printed circuit board (PCB) inside an electronic device. However it was Dietmar who pointed out effects on the actual silicon (or chip) on the PCB during a system-level ESD strike.

“Chip designers and developers previously said they couldn’t solve application issues, but this methodology proves that chip design can be influential,” he said. “It means we’re now solving application problems that we couldn’t before.”

A large number of TI MSP microcontrollers (MCUs) benefit from Dietmar’s research. In fact, it also enabled TI customers to pass tests mandatory for electronic devices certification in Europe, helping save a lot of time and money in development.

Not only did Dietmar solve a variety of customer issues with this one technical characterization process, but he helped to make TI products more robust and more competitive. The unyielding desire to learn – not discouraged by failure —and hard work paved his way to success.

“To Dietmar, learning means doing, and vice versa,” explains Dominik Giewald, his product line manager. “He always tries to harmonize theory and practical applications and to evolve both.”

Multiplying knowledge

“With his high level of personal engagement, enthusiasm and technical leadership, Dietmar is able to learn on an individual level but to also achieve a TI-wide learning success that has a direct impact on our microchips’ resilience,” Dominik said. “To Dietmar, learning doesn’t mean only learning for himself but also sharing, so new innovation can have a broad effect and thus increase the beneficial effect for TI.”

Dietmar places strong emphasis on multiplying the knowledge he has acquired during his decade at TI. He learned a lot from more experienced colleagues and would like to pass his knowledge on to future TIers, including interns and university students whom he mentors.

“If you do not share your knowledge, people have to learn things the hard way,” he says. “You may find 1,000 ways to not invent the lightbulb, but sharing your discovery with others and the path that brought you there will keep them from doing the same 1,000 futile attempts.”